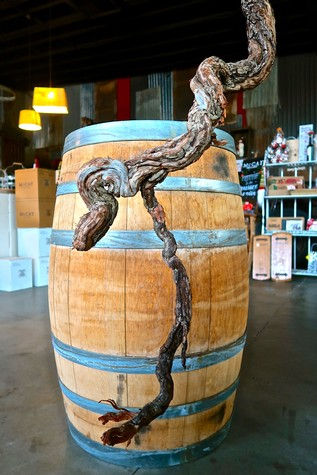

Own-rooted vs. grafted old vine growths

The defining attribute of Lodi's Mokelumne River Viticultural Area is its sandy loam soil, classified in the Tokay series. The appellation's dependably warm, sun-soaked Mediterranean climate has just as much impact, and this watershed area's location between the snow masses of Sierra Nevada and the wetlands of the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta has given farmers plenty of access to water for well over 100 years.

Is it any wonder that Lodi has more acreage of wine grapes than anywhere in the U.S.—more than Napa Valley and Sonoma County, or all of the states of Washington and Oregon, combined? Or in respect to San Joaquin County's other leading crops: Most of the walnuts and almonds are grown in California (California grows 99% of the walnuts in the U.S. and 80% of the entire world's almonds).

These natural conditions are also why Lodi is known for thousands of acres of old vine plantings that are "own-rooted"—cultivated on their own, natural rootstocks. Outside of Chile's Valle Central and South Australia, there are more own-rooted vines in Lodi than anywhere else in the world.

The reason why most of the world's grapevines are grafted onto selected rootstocks (depending upon the source, over 80% or 90%) is because of a near-microscopic root louse called phylloxera, which destroyed most of the vineyards around the world in the late 1800s. Most of the California wine industry outside of Lodi managed to survive by wholesale replanting of vineyards on phylloxera-resistant rootstocks such as St. George, culled from a native American grape bush (Vitis rupestris) renamed after a Southern French town (Saint-Georges'd'Orques) where usage of rupestris proved to be very successful during the 1890s.

Most of Lodi's existing old vine plantings—that is, vineyards planted between the late 1800s and early 1960s—have remained cultivated on their own natural roots, rather than grafted. Some of the few exceptions of note include Steacy Ranch (planted in 1907), Rous Vineyard (1909), and Wegat Vineyard (1956), all grafted on to St. George rootstock when originally planted.

The good majority of Lodi's most acclaimed old vine plantings are own-rooted. Examples found on vineyard-designate bottlings include Marian's Vineyard (1901), Lizzy James Vineyard (1904), Charlie Lewis Vineyard (1903), Royal Tee Vineyard (1889), Spenker Ranch (1900), Kirschenmann Vineyard (1915), DeLuca Vineyard (1961), Mule Plane Vineyard (late 1920s), Peirano Estate (late 1890s), to name a few.

Which brings up the question: If most of Lodi's old vine plantings are root-rooted, does this mean own-rooted vines are superior to grafted old vines? As far as we know, no one can tell. Mostly because the terroirs of individual sites are so distinctive. Slight variations of soil content and depth, vineyard block microclimates, the endless grower and winemaker decisions made throughout each season, and the entire history of each vineyard's farming practices can add up to differentiations that have as much or more impact on profiles of resulting wines as rootstocks.

It is, simply, impossible to correlate factors such as quality, yield, or sensory distinctions—full body/lighter body, zesty acidity/lower acidity, stronger tannin/softer tannin, red fruit/black fruit/blue fruit/herby green fruit, et al.—directly with a choice of whether to graft a vineyard or not was made (in the case of Lodi's long history) over 50, 75 or 100 years ago.

What we do understand are two observable factors:

Vitis rupestris and other rootstocks derived from American grape plants have a natural resistance to phylloxera.

It is possible for the natural roots of Vitis vinifera—that is, the grape species consisting of well-known cultivars that originated in Europe, such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Chardonnay, Pinot noir, Zinfandel, Albariño, Tempranillo, etc.—to thrive with a minimum of effects from phylloxera under special circumstances. Even so, own-rooted old vines that appear to be healthy and productive are never really 100% resistant to phylloxera, no matter where they're grown.

In fact, there is plenty of evidence supporting the fact that, even in the case of Lodi, own-rooted vines are co-existing with phylloxera rather than maintaining a complete resistance. To a large degree, the presence of phylloxera probably plays a large part in the growth and, ultimately, the fruit quality and profiles of wines grown even in older, well-known own-rooted vineyards in Lodi.

Phylloxera observations in California

Despite the apparent longevity of own-rooted plantings in wine regions such as the Sierra Foothills, Lodi, and throughout the multi-county San Joaquin Valley, phylloxera does in fact exist, and can still have debilitating effects on older vines. In a Delta Farm Press (July 25, 2018) report, Tim Hearden quotes University of California Cooperative Extension farm advisor Lynn Wunderlich, who says that longtime growers are often "taken aback by the discovery of phylloxera in their own-rooted vines."

Wunderlich reminds everyone: “Phylloxera is native to North America, so no, we did not get phylloxera from France. Rather, we unwittingly gave it to the Europeans—for which they will never forgive us.

"The pest prefers heavy clay soils that are found in the cooler grape-growing regions of the state, such as Napa, Sonoma, Lake, Mendocino, and Monterey counties, as well as the Sacramento-San Joaquin River Delta region and the foothills. While grape phylloxera can be found in the heavier soils of the San Joaquin Valley, damage may not be as severe."

Wunderlich explains that phylloxera wreaks havoc by causing the swelling of grapevine roots. "Their feeding damages the root system so that fungi can infect and decay the roots, which is why phylloxera-infested vines are so stunted and stressed... After a while, they have little functional root system left."

Wunderlich also points out that, while in the late, 1800s grapevine breeders developed hybrids of other Vitis species for rootstocks such as V. rupestris and V. riparia, these rootstocks "are resistant to phylloxera... but are not immune."

Grapevine phylloxera defenses in San Joaquin County

In a June 3, 2020 issue of San Joaquin Valley Trees and Vines, UC Cooperative Extension Viticulture Advisor Karl Lund talks about seeing phylloxera in own-rooted vineyard blocks in Madera County in 2019. Lund reminds growers of the importance of having a basic understanding of phylloxera, starting with its identification in the field.

Lund cites three major signs: "Galls [i.e., wart-like swellings] on the leaves, nodosities [swellings] on young undignified roots, and tuberosities [rounded swellings] on mature lignified roots... Different grapevine species also succumb to different feeding types.

"While phylloxera is not microscopic, they are very small... Adult phylloxera can get to approximately 1 mm (0.04 inch) in length, while eggs are only 0.3 mm (0.01 inch) in length"—difficult to distinguish "from oddly shaped sand particles."

Phylloxera is most destructive, says Lund, when feeding on mature lignified roots. "In tuberosity... the infestation site swells and cracks allowing for secondary soil fungi to enter the mature root system. These fungi are normally not able to penetrate the lignified root systems, and once inside can cause the roots to start rotting. The infestation site eventually dies off, but not before large numbers of phylloxera eggs have been produced to infect more of the mature root system. As tuberosities can form on lignified roots, it affects all portions of the root system, eventually leading to the collapse of the entire root system and vine death."

All varieties of Vitis vinifera are susceptible to tuberosity formation. However, V. vinifera in Lodi and other parts of San Joaquin County has long been known to have natural defenses. According to Lund, "The first of these is soil type. For a reason that is still unknown, phylloxera has problems infesting roots in sandy soil. As many soil types within the San Joaquin Valley are sandy, this does give a natural defense to vineyards on sandy soil."

The second line of defense is high soil temperature. According to Lund: "Phylloxera eggs, and especially crawlers, have a limited range of temperatures in which they can survive. The work done by Grannet and Timper (1987) has shown that when crawlers get above 90° F., or below 61° F., their survival drops below the level required to maintain population size. When temperatures are outside of this range phylloxera populations will diminish as the life cycle will be broken."

Grannet and Timper's research tracked soil temperatures in different parts of California. Says Lund: "They found that: vineyards in Monterey County saw 9 continuous months with temperatures permitting phylloxera population growth.... vineyards in Mendocino County saw 7 continuous months with temperatures permitting phylloxera population growth, while Fresno County only had temperatures within the correct range for phylloxera population growth for 3 months in the spring and 3 months in the fall...

"This gives Fresno, and the rest of the San Joaquin Valley an advantage when controlling phylloxera. The natural temperature extremes in both the summer and winter prevent phylloxera populations from exploding as they can in many other portions of California. It is not a death blow to phylloxera.

"The temperature readings used in the study were taken at almost 8 inches in depth (for Fresno). Soils deeper down will be exposed to fewer temperature extremes. Grape roots can penetrate much deeper than 8 inches, and the phylloxera will follow. These deeper depths would give phylloxera a refuge to hide in during the hotter and colder portion of the year."

Lund makes note of the fact that, historically, there is one traditional farming practice that has also helped control phylloxera throughout San Joaquin Valley, and that is flood irrigation. While flood irrigation is still practiced in many vineyards in Lodi, drip irrigation has become the predominant method of irrigation. For instance, Bechthold Vineyard—Lodi's oldest existing vineyard (consisting of Cinsaut planted in 1886)—is still flooded through furrows fed by Woodbridge Irrigation canal water for several weeks following each harvest. This has helped these own-rooted vines resist phylloxera throughout its 136-year-old history. Otherwise, Bechthold Vineyard is dry farmed through the rest of each year. Many old vine plantings in Lodi, however, are furrow irrigated throughout the year.

Writes Lund: "During the phylloxera invasion of France in the late 1800s it was found that flooding a vineyard with 40 cm. (15.75 inches) of water for 40 days was effective at reducing phylloxera populations. This is partially due to an interesting combination of biology and physics. For small organisms, the surface tension of water can be stronger than the organisms themselves. Due to this, many insects evolved a layer on their exoskeleton that repels water... phylloxera skipped this advantage. Water droplets stick to phylloxera with such strength that as the water droplet grows it easily surrounds and eventually drowns the phylloxera."

Deep rooting defense mechanism of own-rooted vines

Grapevine response to phylloxera in Lodi's exceptionally deep—50 to over 90 feet in most parts of the region's Mokelumne River AVA—Tokay series sandy loam terroir has also been observed by this ramification: Taproots of own-rooted old vines penetrating as far down as 40, 50 feet.

Mike McCay, owner/grower/winemaker of Lodi's McCay Cellars, shared a recent experience of pulling out a 100-year-old Zinfandel plant while digging a pit in his Lot 13 Vineyard. Says Mr. McCay: "When we pulled out the vine we found that there wasn't so much a root system as a taproot that was 2 inches wide at about 5 feet below the ground, and still 2 inches wide at about 25 feet, which was about where we stopped digging. At that point, there were a couple of feeder roots, but obviously, the taproot was going down much deeper, which is probably where we would've found a more extensive root system."

Adds Mr. McCay: "I'd argue that these 100-year-old Zinfandels tap into whatever water sources they can find, sending their taproot through all the permutations in that sandy soil, including a few layers of limestone we found beneath Lot 13. I still don't know exactly how far down the roots go, but I can tell you that in a typical growing season we'll water just once, and the vines remain perfectly healthy and productive all the way through. This is completely different from my trellised vineyards on drip systems, where roots go down only about 6 feet, and you have to constantly monitor to keep things going."

In a discussion of his ZinStar Vineyard estate—own-rooted Zinfandel planted on Mokelumne River-Lodi's west side in 1933—The Lucas Winery's owner/grower David Lucas has recently commented: "The effect of phylloxera even on vineyards that are still doing well on their own roots is apparent because these plants do not really have an extensive root system just below the surface, where the root louse is more active. Vines affected by phylloxera are forced to develop deep, strong roots to find water and nutrients. In the case of Lodi, this is possible because of our extremely deep, sandy soil.

"That's another reason why we work so hard on soil health [The Lucas Winery is certified both organically and sustainably]. Our wines are the result of a combination of what nature gives us and how we farm. Both factors go hand in hand. That's why we are known for our old vine wines in Lodi!

Randy Caparoso is a full-time wine journalist who lives in Lodi, California. Randy puts bread (and wine) on the table as the Editor-at-Large and Bottom Line columnist for The SOMM Journal, and currently blogs and does social media for Lodi Winegrape Commission’s lodiwine.com. He also contributes editorial to The Tasting Panel magazine and crafts authentic wine country experiences for sommeliers and media.

Comments